From Terracotta to Plastic

An antefix is a vertical fixture that abuts the edge of the tiled roof. A common feature of buildings of the classical period, these architectural elements were often decorated, sometimes elaborately. This moulded and painted copy of a striking second-century antefix in the form of a gorgon’s head was created from a digital 3D model produced by the Institute for Digital Archaeology and used in the recent film Freud’s Last Session starring Sir Anthony Hopkins. The terracotta original can be seen at the Freud Museum in London where it still sits on Freud’s desk. Freud was a pioneer in the psychology of “object relations” — the relationship between people and inanimate objects. He was, moreover, fascinated by the art and architecture of the classical world, amassing in his lifetime a substantial collection of antiquities.

This item was loaned to us for the physical exhibition by the Freud Museum, London. Institute for Digital Archaeology (2023). Roman antefix in the form of a Gorgon’s head. Replica of terracotta original (c. 2nd century AD).

The Elgin Marbles Revived

This statue is an exact recreation of the head of the Selene Horse, part of the East Pediment of the Parthenon Sculptures — the so-called Elgin Marbles — currently displayed in the British Museum and dating from the fifth century BC. It was fabricated by the Institute for Digital Archaeology (IDA) in 2022 in the workshop of their Italian partners Robotor, as part of ongoing efforts to resolve the two-hundred-year-old dispute between Greece and Britain over custody of the Parthenon Sculptures. It was unveiled for the first time at the Freud Museum in London in November 2022.

The reproduction was crafted using a high-resolution 3D digital model of the original sculpture and carved robotically from the same rare Pentelic marble. The use of Pentelic marble is controlled by the Greek Government on account of its cultural significance and the high demand for the material for repairs to heritage structures. This is the first time the material has been used in a project outside of Greece.

This item was loaned to us for the physical exhibition by the Institute for Digital Archaeology. Institute for Digital Archaeology (2022). Full size replica of Phidias’s Selene horse. Pentelic marble.

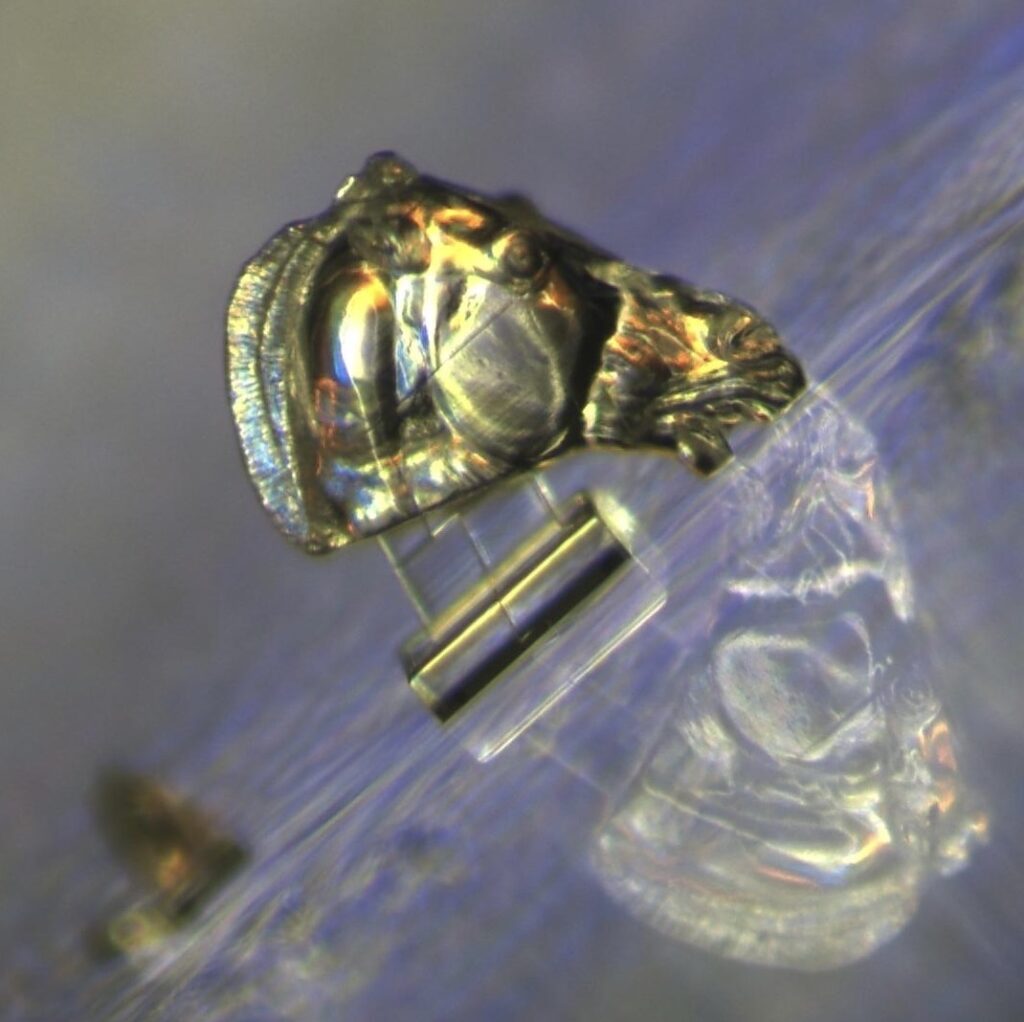

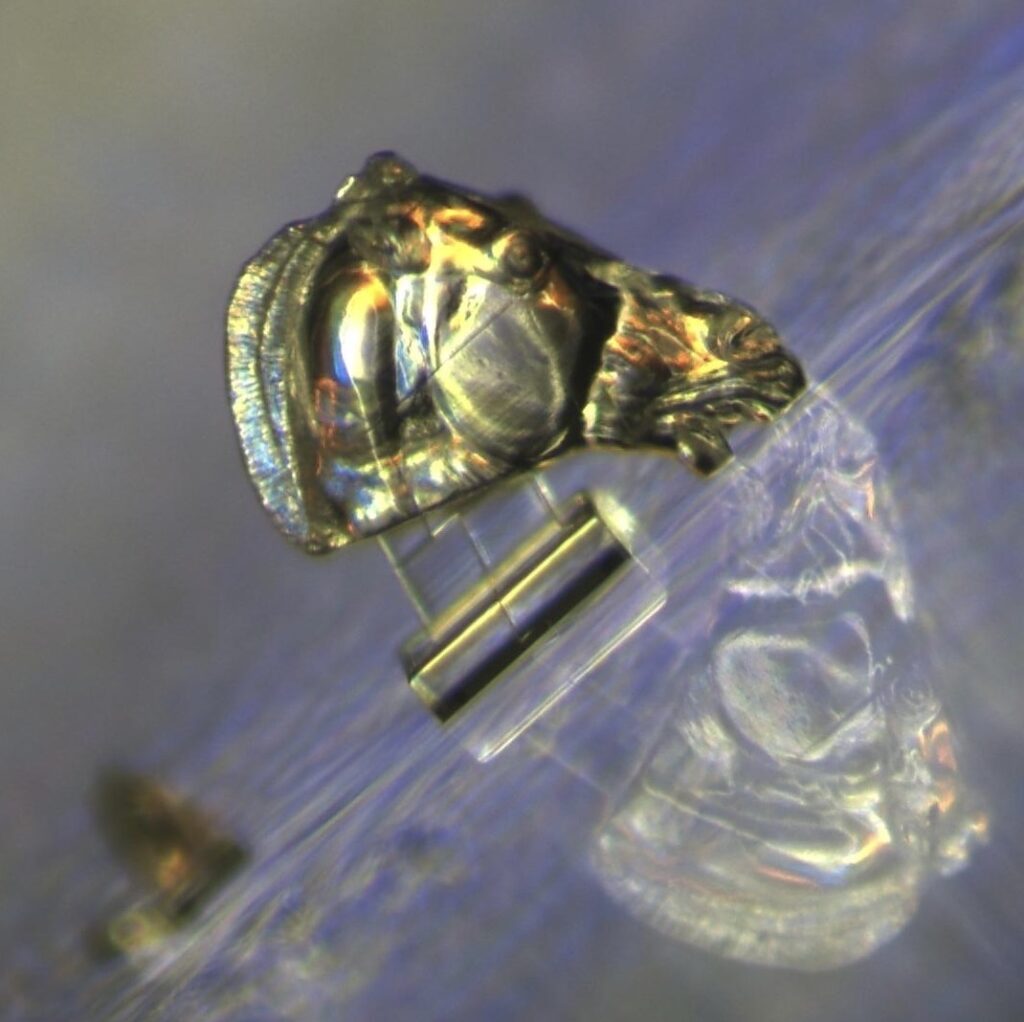

Under the Microscope

As long as humans have had the ability to make things — and to appreciate things that have been made — we have been fascinated with scale. Pushing the limits of the massive and the miniature is a longstanding trend in almost all areas of constructive human activity, from animal husbandry to astrophysics. When applied to heritage objects, the act of miniaturisation raises an interesting set of questions. At a time when the creation of virtual versions of the world around us has moved into the realms of the trivial — inexpensive off-the-shelf tools can now be used to create digital versions of objects and environments of near-Hollywood quality — there remains something inherently interesting about real-life physical reproduction.

The question of authenticity when applied to copies of three-dimensional objects has attracted interest since the nineteenth century — the heyday of the copy-artist. At that time — the era of plaster casting and electrotyping — it became fashionable both to augment museum collections and to dress private homes with high-quality copies of otherwise inaccessible or unaffordable classical masterpieces. This trend for copying took in a full range of ambitions, from the modest to the monumental. The 1897 Tennessee Centennial Exposition saw a full-scale replica of the Parthenon constructed in Centennial Park, Nashville — a building that stands to this day.

In this context, the sticky matter of the relationship of a copy to an original object is one that attracts strong views. Some take the position that a copy of an object — no matter how good — can only ever be a poor relation of the original version. Others take an opposing one — that the value of the original object resides solely in its aesthetic qualities and that a copy — so long as it is a fine one — is just as good as the original. Most sit on a fence somewhere in-between — recognising that copies are helpful repositories for information, yet still having a preference for being in the presence of the real thing.

And so the question of where the culture resides; in a specific physical manifestation of something original — whatever that means — or in the sum-total of the information that makes it up is an eternally interesting one.

The process of miniaturising a highly recognisable cultural object such as the Selene horse brings this interesting philosophical question into sharp focus. By making a perfect copy so small that it cannot be seen by the naked eye, have we condensed the cultural value of that object into a tiny portable package, or simply created a new object that is no more interesting than an homage to the original? Do we need to be able to actually “see” the detail of a copy of a known object to recognise it as a representation of that object and find it valuable, or does it suffice simply to know that it is there?

This item was loaned to us for the physical exhibition by the Institute for Digital Archaeology. Institute for Digital Archaeology (2023). Miniature Selene horse. A copy of the original just three human hair widths high.